Getting Started

- About Us

- Getting Started

- Basic Algebra

- Metric Prefixes

- Trigonometry

- Index/Glossary

Mechanics

Kinematics

- Vectors

- Dimensional Analysis

- Position, Velocity, Acceleration

- One-Dimensional Motion/Free fall

- Two-Dimensional Motion/Projectile Motion

- Relative Velocity

Dynamics

- Newton's Laws

- Forces

- F=ma and Free-body Diagrams

- Inclined Planes and Pulleys

- Spring Forces

Circular Motion and Gravitation

- Centripetal Force/Acceleration

- Fictitious Forces

- Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation

- Kepler's Laws

Energy

- Dot Product

- Definition of "Work"

- Definition of Energy and Energy Conservation

- Types of Equilibrium

- Definition of Power

- Universal Gravitational Potential Energy

Momentum

- Impulse/Momentum Theorem

- Conservation of Linear Momentum

- Center of Mass

- Collisions

- Explosions

Rotation

- Rotational Kinematics

- Torque

- Moment of Inertia

- Rotational Dynamics

- Rolling Without Slipping

- Rotational Kinetic Energy and Angular Momentum

Oscillations

- Simple Harmonic Motion

- Spring-Block Oscillators

- Pendulums

- Other Oscillators

Fluids

- Properties of Fluids

- Pressure

- Fluid Flow

- Bernoulli's Principle

- Air Resistance and Drag

Electricity & Magnetism

Electrostatics

- Electric Charge

- Coulomb's Law

- Electric Fields

- Gauss's Law

Thermodynamics

Getting Started

- About Us

- Getting Started

- Basic Algebra

- Metric Prefixes

- Trigonometry

- Index/Glossary

Mechanics

Kinematics

- Vectors

- Dimensional Analysis

- Position, Velocity, Acceleration

- One-Dimensional Motion/Free fall

- Two-Dimensional Motion/Projectile Motion

- Relative Velocity

Dynamics

- Newton's Laws

- Forces

- F=ma and Free-body Diagrams

- Inclined Planes and Pulleys

- Spring Forces

Circular Motion and Gravitation

- Centripetal Force/Acceleration

- Fictitious Forces

- Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation

- Kepler's Laws

Energy

- Dot Product

- Definition of "Work"

- Definition of Energy and Energy Conservation

- Types of Equilibrium

- Definition of Power

- Universal Gravitational Potential Energy

Momentum

- Impulse/Momentum Theorem

- Conservation of Linear Momentum

- Center of Mass

- Collisions

- Explosions

Rotation

- Rotational Kinematics

- Torque

- Moment of Inertia

- Rotational Dynamics

- Rolling Without Slipping

- Rotational Kinetic Energy and Angular Momentum

Oscillations

- Simple Harmonic Motion

- Spring-Block Oscillators

- Pendulums

- Other Oscillators

Fluids

- Properties of Fluids

- Pressure

- Fluid Flow

- Bernoulli's Principle

- Air Resistance and Drag

Electricity & Magnetism

Electrostatics

- Electric Charge

- Coulomb's Law

- Electric Fields

- Gauss's Law

Thermodynamics

F=ma and Free-body Diagrams

Introduction

Newton’s Second Law is the most important and most difficult of all his laws to master. To learn how to use force analysis to get quantitative results, we first need to understand what a net force is. The net force is simply the vector sum of all the forces acting on an object, written as $F_{net}~\textrm{or}~\Sigma F$, where $\Sigma$ indicates summation. However, it is usually more useful to have two net forces directed along two axes.

Free-Body Diagrams

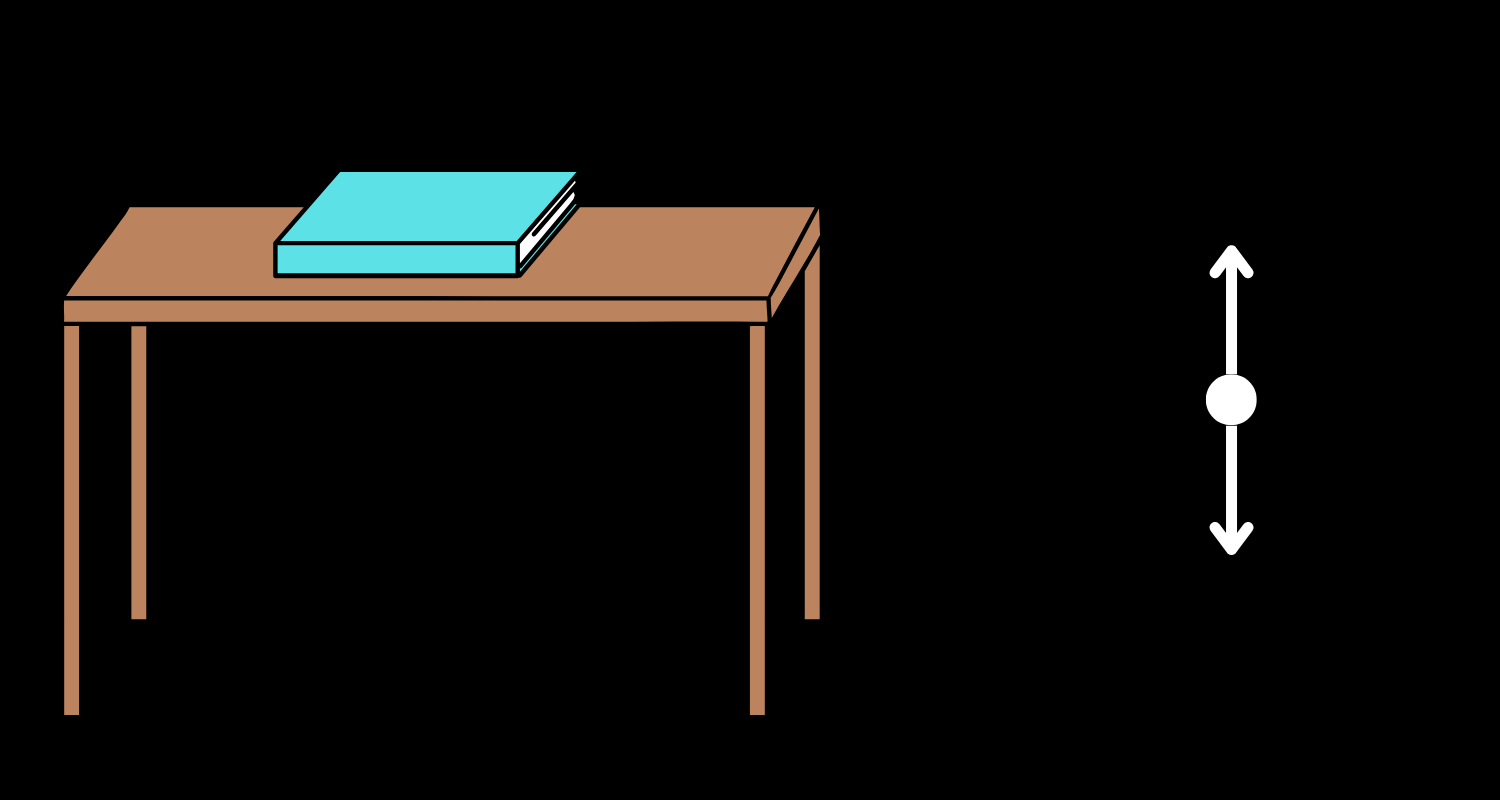

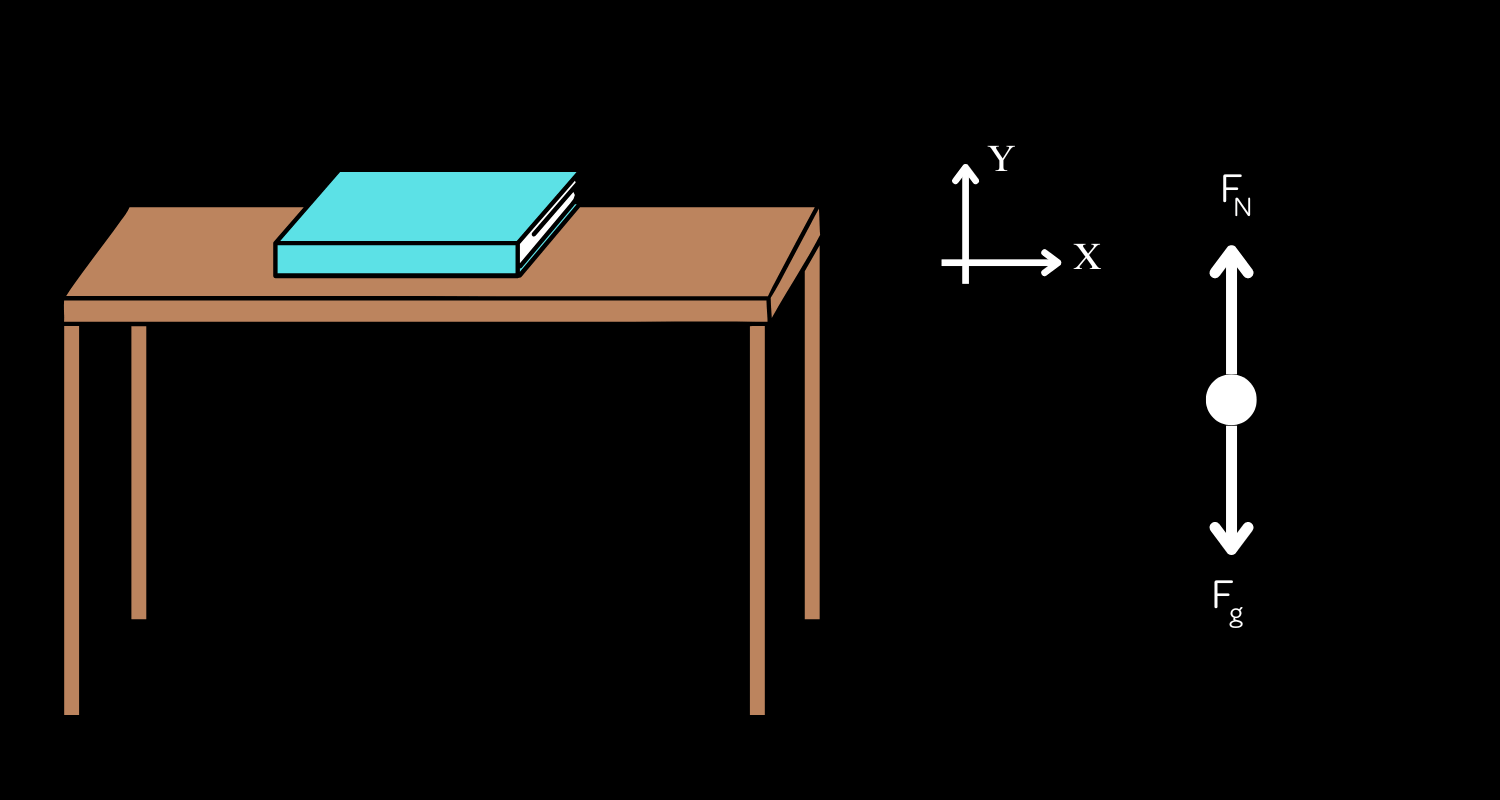

To represent forces on an object, we will use the free-body diagram (FBD). To construct an FBD, we consider the object as a point and draw the forces acting on it with their tails on the point. For instance, consider the case of a book on a table. Remember that forces are vectors, so their magnitude and direction matters! A free-body diagram is essentially just a diagram of a singular body, or system, and all the EXTERNAL forces.Here is an example:

Did you get it? The force down should be gravity, but the book is not moving, so there is an upward force, and that is the normal force from the table!

Now seeing after how to NOT draw an FBD, we will give you a (mostly) foolproof recipe on how to build a correct FBD that will help you solve even the most difficult of problems!

How to Construct FBDs

- First, we want to define a body or system and a reference frame to work in. Essentially, this part is isolating the body and determining what coordinate axes we want to use. For example, on a slope, we might want to use an axes parallel to the slope. You can typically use any axes, but generally go for the ones that most of the forces are aligned on or one that pertains specifically to the question.

- Next, have a list of all the forces you will need to draw. You can simply go off this list and draw the forces if they exist. Gravity, friction, the normal force, drag (usually air drag), tension, and all other forces. A good rule of thumb is that if the force is not explicitly stated to exist in this scenario, assume it exists. For example, if a problem says "a wall", assume there is friction on the wall. Another key thing is to note that there are specific key words that implies something, like "a smooth wall" implies frictionless, and "from rest" means $v_0=0$. Recognizing these terms are important for doing physics problems correctly!

- The final step is to draw those forces. Start by representing the body or system as a dot. Draw all the forces from the dot, taking in account their directions (forces are vectors!), and try to keep the sizes are relative as well (if the force has twice the magnitude of another make it twice as long as that one). Remember to also draw the correct orientations for your coordinate axes as well. When you're finished, your drawing should look like the one above.

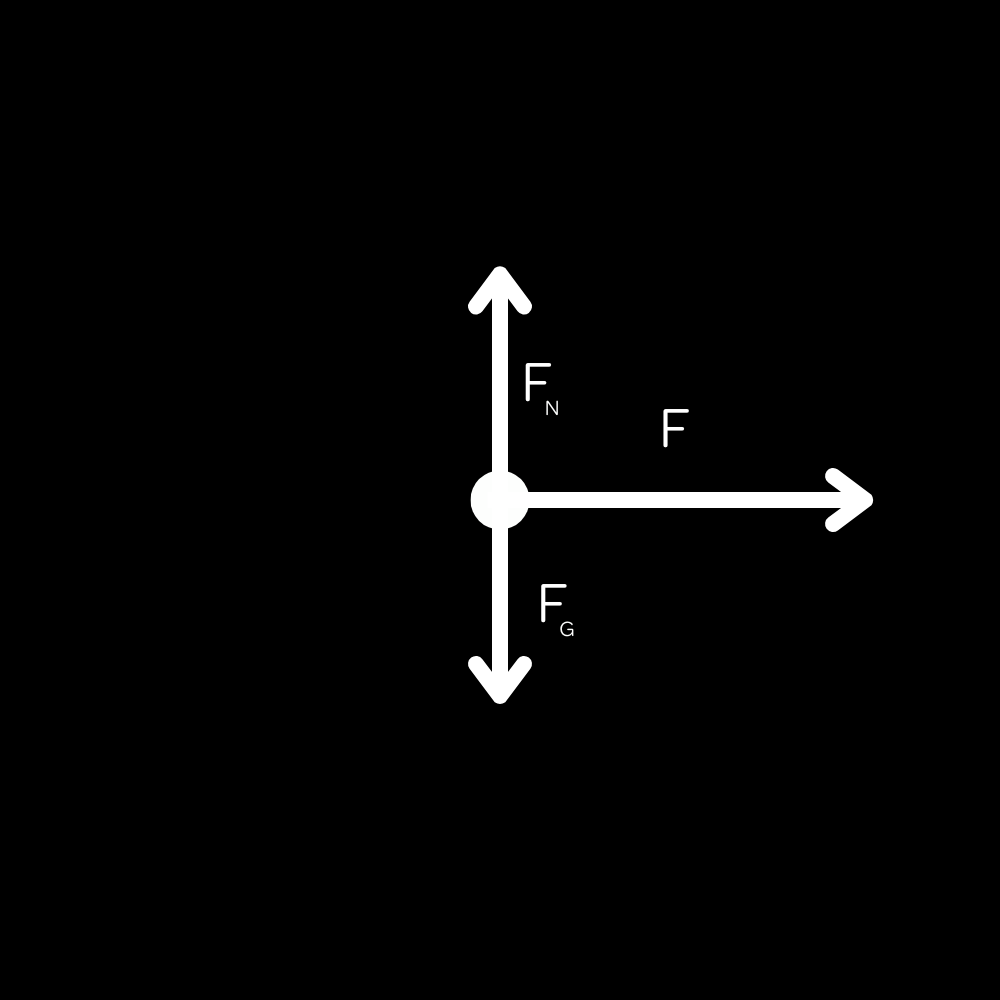

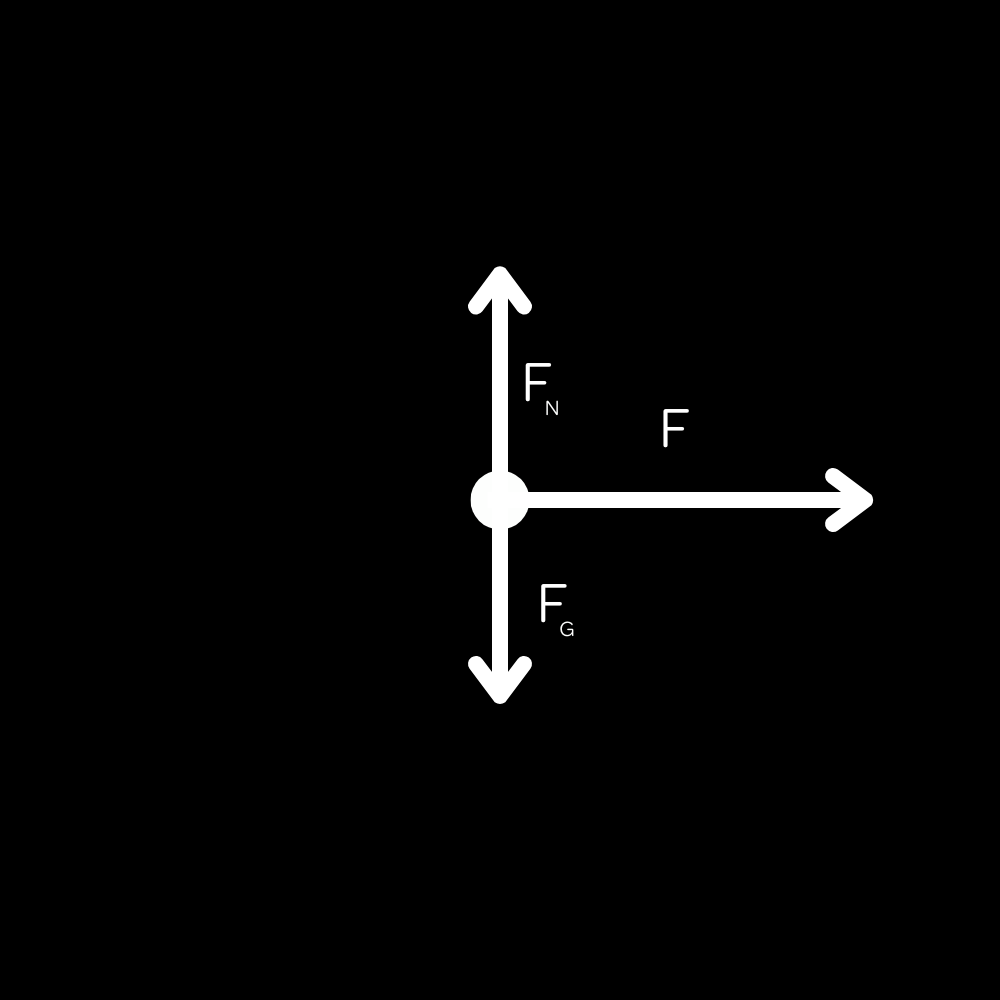

Hopefully, we recognize that there are three forces present: the gravitational force, the normal force from the ground, and the applied force (also technically a normal force) from Bob. It can be easy sometimes to forget that the normal and gravitational forces are going to be present in the FBD, even though they are not mentioned in the problem.

Now I know just talked about how the normal and gravitational forces are present, but in this case they are not actually important for the problem. Intuitively, we know that the cart doesn't accelerate vertically, so the normal and gravitational forces must be balanced. Therefore, we only need to apply Newton's Second Law in the horizontal direction, where only one force is present.

$F_{net,x} = F = 50~\textrm{N}$

We can now easily use algebra on Newton's Second Law to find the acceleration of the cart.

$m = 15~\textrm{kg}$

$a = \frac{F_{net,x}}{m} = \frac{50~\textrm{N}}{15~\textrm{kg}} = 3.33~\textrm{m/s}^2$

Now, I'll ask a few conceptual questions on the problem to make sure you understand the concepts. This is really commonly seen with multi-part physics problems, either in textbooks, homework, or exams, so it is important to be able to answer these questions. They are also not too difficult, so you should be able to answer them even if you couldn't mathematically solve the main problem.

What if another person pushes the box in the same direction? Qualitatively, how will the acceleration compare?

What about in the opposite direction?

What is the magnitude of the normal force in the above scenario?

Note that there is no way for us to know the velocity of an object through force analysis, just acceleration. We have to be given the velocity at some point in time in order to solve for velocity at any other point. If you want to get fancy, this principle is called Galilean Relativity, which states that it is impossible to determine absolute velocity of any given inertial reference frame. Another key tenet of the idea is that the laws of physics are the exact same in all inertial reference frames, which turns out to be true. Galilean Relativity is very important in Newtonian physics, and is the reason why we can only determine acceleration through force analysis. But it also turns out to be incorrect in its assumption that time is independent of velocity, which is a key tenet of Einstein's Special Relativity. But that's something that's way too advanced for right now. (Eric wrote this part, so if you have any questions about it, ask him.)

As we are more focused on concepts here, we will not be going into mathematical computation of this problem. Instead, we can simply focus on the conceptual understanding of how to draw a proper free-body diagram of this problem, as well as qualitative analysis of it.

Now, conceptually we should understand why each force is present, and their relative magnitudes. You may have forgotten to include the normal and gravitational forces, a common mistake when motion vertically isn't mentioned or involved. However, in almost all scenarios, the gravitational force is present, and the normal force is present in a large number of scenarios as well. The proper FBD needs to include these to be correct even though they do not affect the motion of the cart because all forces need to be present. Now, the applied force $F$ is present for obvious reasons (it's applied to the cart by Bob). Since we said no friction (which is usually assumed if not explicitly stated, by the way), the only force acting on the cart in the horizontal direction is the applied force.

Therefore, the total net force is equal to the applied force and in the horizontal direction, since the forces in the y-direction are balanced. (This is because the cart is not moving into or out of the ground, so the forces must be balanced in that direction.) According to Newton's Second Law, we can therefore conclude that there will be a net acceleration horizontally, in the direction of the applied force. The exact calcuation is simple, but not necessary for a good conceptual understanding of the problem.

Now, for a some conceptual questions. What if another person pushes the box in the same direction? Qualitatively, how will the acceleration compare?

What about in the opposite direction?

What is the magnitude of the normal force in the above scenario? Give a conceptual answer, not a numerical one.

See? This unit isn't so bad, right? You can do it! Just remember to always draw the free-body diagram first, and then analyze the forces. If you feel confident, you can move up to one of our more advanced levels, where we will do quantitaive analysis of this problem and many more. If you don't feel prepared, don't worry! You can always come back to this lesson later when you feel ready to tackle the math.

Now that we have a good understanding of how to draw free-body diagrams, we can start throwing more complex things into the mix. Here, we will introduce an old friend all the way back from the last lesson, the frictional force. We'll start simple:

The key is to understand that the static frictional force will equal the applied force up until a certain thereshold. The maximum static frictional force is equal to $F_{s, max} = \mu_s F_n$, where $F_n$ is the normal force. Therefore, the applied force must be at least this large to overcome the static frictional force and begin to move the object. We also have to consider the normal force, but since the object is on a horizontal surface, the normal force is equal to the weight of the object, $F_n = mg$.

Therefore, our final answer is $F = \mu_s mg$. This is a pretty clean and neat result!

This one is definitley slightly more complex. Seeing as this unit is about forces and mass is literally one of the three components of Newton's Second Law, you may think that we are missing a crucial piece of information: the mass of the object. But, as it turns out, we don’t need it. We will still use the variable m to denote mass in our equations, but in the end you will find that its value is not needed. It's a surprise that will reveal itself later.

In this case, we can intuitively see that $mg=F_N$. But this will not always be the case in the future, particularly in the next lesson! Friction is the only force acting in the horizontal direction. We can then write:

$F_{net}= \mu_k mg$

We then use the second law to write:

$ma=\mu_k mg$

$a=\mu_k g$

Notice how the mass has canceled out!

This time, I’ll leave the algebraic plugging in to you, or you could decide to plug these variables in for $a$ in subsequent equations (which is what I will do). From now on, you’ll notice that I begin to solve problems more generally instead of using specific values. It’s good practice to solve any problem generally and disregard numbers until the end, at least for now. Why is this? Some more complicated problems can be simplified greatly by finding the value of some intermediate quantity. Furthermore, it is easy to lose track of values you substituted into an equation. You might have noticed that with the trajectory formula back in projectile motion, where the end equation solved generally had a very generous amount of quantities to plug in.

After getting $a$, we can easily use our kinematics knowledge to find the answer:

$v_f=v_0-at$

$v_0=at$

$t=\frac{v_0}{\mu_k g} = 3.40 ~\textrm{s}$

Those two problems were simple enough. Now, we'll move on to another friction example, this time showing something that might not be immediately obvious. Now we should consider a slightly more complex problem involving friction.

Now, think about this problem in the real world. When you push lightly on a book that sits on a tabletop, it doesn't immediately start to move. This might help you visualize the problem more clearly. You should also attempt to create a free-body diagram for this scenario. Here's a little hint: the total number of forces acting on the body is four.

Did you get it? Think back to our last lesson, where we briefly discussed static and kinetic friction. You needed to remember how the key idea behind static friction in this case is that it will equal your applied force up until a maximum value defined by $F_{s, max} = \mu_s F_n$. This is the minimum force that you must apply for the object to start moving. By this logic, the force that you have to push with is:

$F = F_{s,max} = \mu_s mg$ (because the normal force is equal to the gravitational in this case)

That wasn't so difficult, was it?

Now, what happens for an object that is already sliding against a surface? In other words, what if kinetic friction is at play instead?

For kinetic friction, the value is always $F_k = \mu_k F_n$. This indicates a constant force acting on whatever object we are interested in, opposing the direction of motion. In our scenario, there are no other forces present acting on the system. See if you can use this information to create a general FBD for the scenario.

This is actually just a case of constant acceleration, as you might have concluded. The force acting on the system in the horizontal direciton is constant because kinetic friction takes a constant value, and the mass is constant as well. Therefore, according to Newton's Second Law the acceleration of the system is constant and directed in the opposite direction as the direction of motion, tending to slow down the object until it comes to rest relative to whatever surface it is sliding on.

Now, what would happen if the surface it was on was also moving? This is where things get interesting.

We have gone over two friction examples already, but we now should consider friction for a body in motion. See, friction doesn’t always oppose motion, just relative motion between two surfaces. Friction can actually cause something to start moving.We will consider the following scenario in order to have a better understanding of this.

$F_{net} = F_s = \mu_s F_n$

$F_n = mg$

$a_{max} = \mu_sg$

Now something a lot of people, you included, might wonder is how the friction force can be pointing in the direction of motion. Doesn’t friction tend to oppose motion? Well, that is correct to a certain extent, but not specific enough. Friction only tends to oppose relative motion (since absolute motion doesn’t actually exist, according to Einstein and Galileo). To do that in this case, it has to accelerate the penguin at the same rate (or try to) as the sled so the two don’t move relative to each other.

Now to consider the second part of the problem. To find acceleration caused by a force $F$, we actually have to find two accelerations. First, we consider the no-slip case, where $a \leq \mu_sg$. I’ll use the technique of treating each body individually to show that they can be treated as one body.

For the penguin, we have:

$F_{net}=\mu_sm_pg=m_pa$

For the sled, we have:

$F_{net}=F-\mu_sm_pg=m_sa$, where we include the reaction force of the friction on the penguin (equal in magnitude and opposite in direction!)

Now, we can add the two equations:

$(m_s+m_p)a=F$ ($a$ has the same value in the two equations because there is no relative motion)

$a=\dfrac{F}{m_s+m_p}$

This is the same as if we treated the two bodies as one, with a total mass of $m_s+m_p$ and ignoring all internal forces (forces that act between objects in the system).

Now, what if the penguin slips on the sled? In that case, friction is kinetic, and we can no longer treat the two objects as one because they are moving relative to each other.

$F_k=\mu_k m_pg$

Since the two bodies are now no longer moving together, we only consider the body we want the acceleration of: the sled.

$F_{net}=F-\mu_sm_pg=m_sa$

$a=\dfrac{F-\mu_sm_pg}{m_s}$, which is a lot less elegant than the no-slip solution! Conclusion

Now that we've covered the types of force-analysis problems requiring FBDs briefly, we can talk more in-depth about two common special types of force-analysis problem in the next lesson.

Now, we know that the penguin and sled can move together if you just pull on the sled, but what causes the penguin to move in this case? The pulling force is applied onto the sled and not the penguin, after all. Friction is what actually comes to save the day. See, friction doesn’t always oppose motion, just relative motion between two surfaces. Therefore, it will try to keep the penguin from sliding off the sled.

This gives rise to an interesting conclusion. If friction is keeping the penguin moving with the sled, this means that friction must actually act to accelerate the penguin! The frictional force on the penguin must be in the same direction as the applied force on the sled. This means the friction is actually causing the penguin to move, which can be a shocking conclusion since we typically see friction as a force that opposes motion! A side note of this is that there is a maximum acceleration that the penguin can have before it slips off, because there is only so much force that the static frictional force can provide. This example perfectly illustrates how important carefully reading the exact definitions are, as they can lead to very interesting and unexpected conclusions. Physics is not always intuitive, and some discoveries can come as welcome surprises. Conclusion

Now, we have a good conceptual grasp on how to analyze the forces in a system. In the next lesson, we will go over two very common key examples and general scenarios in forces and beyond. So, without further ado, let's get to it!