Lessons

Problems

Getting Started

- About Us

- Getting Started

- Basic Algebra

- Metric Prefixes

- Trigonometry

- Index/Glossary

Mechanics

Kinematics

- Vectors

- Dimensional Analysis

- Position, Velocity, Acceleration

- One-Dimensional Motion/Free fall

- Two-Dimensional Motion/Projectile Motion

- Relative Velocity

Dynamics

- Newton's Laws

- Forces

- F=ma and Free-body Diagrams

- Inclined Planes and Pulleys

- Spring Forces

Circular Motion and Gravitation

- Centripetal Force/Acceleration

- Fictitious Forces

- Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation

- Kepler's Laws

Energy

- Dot Product

- Definition of "Work"

- Definition of Energy and Energy Conservation

- Types of Equilibrium

- Definition of Power

- Universal Gravitational Potential Energy

Momentum

- Impulse/Momentum Theorem

- Conservation of Linear Momentum

- Center of Mass

- Collisions

- Explosions

Rotation

- Rotational Kinematics

- Torque

- Moment of Inertia

- Rotational Dynamics

- Rolling Without Slipping

- Rotational Kinetic Energy and Angular Momentum

Oscillations

- Simple Harmonic Motion

- Spring-Block Oscillators

- Pendulums

- Other Oscillators

Fluids

- Properties of Fluids

- Pressure

- Fluid Flow

- Bernoulli's Principle

- Air Resistance and Drag

Electricity & Magnetism

Electrostatics

- Electric Charge

- Coulomb's Law

- Electric Fields

- Gauss's Law

Thermodynamics

Lessons

Problems

Getting Started

- About Us

- Getting Started

- Basic Algebra

- Metric Prefixes

- Trigonometry

- Index/Glossary

Mechanics

Kinematics

- Vectors

- Dimensional Analysis

- Position, Velocity, Acceleration

- One-Dimensional Motion/Free fall

- Two-Dimensional Motion/Projectile Motion

- Relative Velocity

Dynamics

- Newton's Laws

- Forces

- F=ma and Free-body Diagrams

- Inclined Planes and Pulleys

- Spring Forces

Circular Motion and Gravitation

- Centripetal Force/Acceleration

- Fictitious Forces

- Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation

- Kepler's Laws

Energy

- Dot Product

- Definition of "Work"

- Definition of Energy and Energy Conservation

- Types of Equilibrium

- Definition of Power

- Universal Gravitational Potential Energy

Momentum

- Impulse/Momentum Theorem

- Conservation of Linear Momentum

- Center of Mass

- Collisions

- Explosions

Rotation

- Rotational Kinematics

- Torque

- Moment of Inertia

- Rotational Dynamics

- Rolling Without Slipping

- Rotational Kinetic Energy and Angular Momentum

Oscillations

- Simple Harmonic Motion

- Spring-Block Oscillators

- Pendulums

- Other Oscillators

Fluids

- Properties of Fluids

- Pressure

- Fluid Flow

- Bernoulli's Principle

- Air Resistance and Drag

Electricity & Magnetism

Electrostatics

- Electric Charge

- Coulomb's Law

- Electric Fields

- Gauss's Law

Thermodynamics

Centripetal Force/Acceleration

Introduction

You often hear of centrifugal force being the force that holds you against the walls of one of those amusement park spinning rides. It is actually quite amusing since centrifugal force isn't a real force (but still exists calculationally) and the real deal behind circular motion is the centripetal force. Both those names are Latin in origin and mean center-fleeing and center-seeking respectively. Finally, some English that makes sense. Note that this is NOT a new force, but really a required force for circular motion to occur. Some have suggested calling this the centripetal force requirement, but I believe that’s a mouthful.Here's a visual demonstration of what I mean by circular motion. Try giving the ball a shove to make it go faster or slower, or try enabling and disabling gravity. There's even a way to make a particle accelerator if you toggle gravity right.

Circular Motion Demo

Centripetal Acceleration

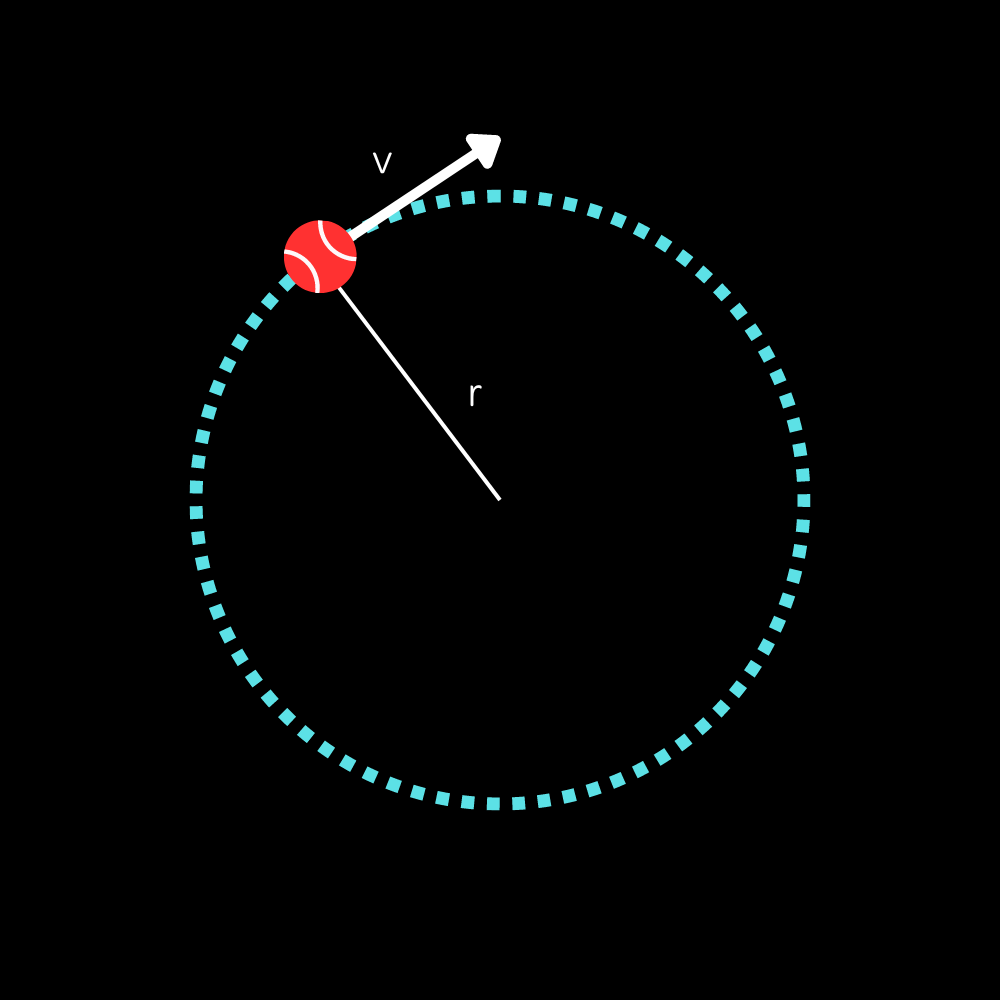

Centripetal acceleration is directed inward toward the center of the circle that the object traces out as it moves. At every point in its motion, the object’s velocity is tangential to the circle, which is why when you suddenly let go of a ball swinging in a circle above your head, it flies off in a straight line. Newton’s first law in action! You should try it yourself! (Note: I am not responsible for any damages you may cause while attempting this activity.) You might be tempted to think that swinging it vertically would be the same, but that case is much more complicated. Here’s a little diagram to sum up this block of text:

$r$ is the radius and $v$ is the velocity of the ball, which is constant in uniform circular motion (hence the name).

Derivation

There’s a good and neat proof for the formula for centripetal acceleration. Consider an infinitesimal time interval $dt$. In that interval, the ball displaces $ds=v dt$ along the circle. But, $ds =r \cdot d\theta$ due to how circles work. (We’re using s since arc length is not displacement.)So we write down:

$$r d\theta=v dt ~(1) $$

Acceleration is defined as:

$$a=\dfrac{dv}{dt}$$

By the same logic as before,

$$dv=v d\theta ~(2)$$ $$a=v\dfrac{d\theta}{dt} ~(3)$$

Substituting (1) and (2) into (3), we obtain:

$$a=\dfrac{v^2}{r}$$

Consider a small time interval $\Delta t$. In that interval, the ball roughly displaces $\Delta x=v\Delta t$ along the circle. There is also a small change in the angle $\Delta \theta$, allowing us to write $\Delta x=r\sin\Delta\theta \approx r\Delta\theta$ by the small angle approximation $\sin\theta \approx \theta$.

We can write:

$$r \Delta \theta=v \Delta t ~(1)$$

Acceleration is defined as:

$$a= \dfrac{\Delta v}{\Delta t}$$

By the same logic as before,

$$\Delta v=v \Delta \theta ~(2)$$ $$a=v\dfrac{\Delta\theta}{\Delta t}~(3)$$

Substituting (1) and (2) into (3), we obtain:

$$a=\dfrac{v^2}{r}$$

The proof for this formula requires some advanced math and reasoning, so we'll just give you the formula here.

$$a=\dfrac{v^2}{r}$$

Centripetal acceleration is more commonly denoted $a_c$ instead of just $a$.

Centripetal Force

By extension, we can write the centripetal force (really the centripetal force requirement) as:$$F_c=m a_c=m\dfrac{v^2}{r}$$

Now, we should analyze this formula. We see that the centripetal acceleration required is higher if the speed is greater, which makes sense. (Try spinning a ball around your head at a high speed versus a slower speed to see this.) We also see that it inversely depends on the radius, meaning the required acceleration is less if the circle travelled is larger. You can also easily prove this to yourself.

You might ask yourself, "What happens if the speed isn't uniform?" Well, the centripetal acceleration has a counterpart, named the tangential acceleration, which is in a direction perpendicular to the centripetal acceleration and tangential to the circle, in the same direction as or antiparallel to the velocity. This is a good concept to know, but doesn't require as much introduction as the centripetal acceleration.

With that, we are ready for some very basic problems. Here is a very simple example to get us started.

What is the required centripetal acceleration to move a ball at $5 ~\textrm{m/s}$ in a circle of diameter $4~\textrm{m}$?

This is just direct substitution.

Answer: $$a_c=\dfrac{v^2}{r}=\dfrac{25}{2}=\bbox[3px, border: 0.5px solid white]{12.5 \textrm{m/s}^2}$$

This is just direct substitution.

Answer: $$a_c=\dfrac{v^2}{r}=\dfrac{25}{2}=\bbox[3px, border: 0.5px solid white]{12.5 \textrm{m/s}^2}$$

Now, we are ready for more complex scenarios. The derivation for the centripetal acceleration is too complex for a conceptual level, but I will show its results Headers. The centripetal acceleration required to keep an object moving at speed $v$ in a circle of radius $r$ is:

$$a_c = \dfrac{v^2}{r}$$

Not too complex, eh? Now, we should analyze this formula. We see that the centripetal acceleration required is higher if the speed is greater, which makes sense. (Try spinning a ball around your head at a high speed versus a slower speed to see this.) We also see that it inversely depends on the radius, meaning the required acceleration is less if the circle travelled is larger. You can also easily prove this to yourself.

Centripetal Force

The centripetal force (again, like friction, NOT a new type of force) required directly builds off of this centripetal acceleration:$$F_c = m\dfrac{v^2}{r}$$

Unfortunately, the majority of uniform circular motion is calculation-based and there is not too much conceptual content. Therefore, this lesson may seem short in comparison to some others, but you can check out our higher levels if you're interested in the mathematics behind circular motion. We are now going to briefly discuss some more scenarios.

We're going to start immediately with a few problems/scenarios that I (Eric) believe are good to introduce key knowledge about this unit.

Consider a bicycle going around a circular track of radius $15 ~\textrm{m}$ at $12 ~\textrm{m/s}$. The bicycle and rider have a combined mass of $70 ~\textrm{kg}$.

a) What is the centripetal force that must be acting on the system?

b) What force supplies this centripetal force?

Part a) is a direct calculation and is quite simple to do.

$$F_c= m\frac{v^2}{r}=672 ~\textrm{N}$$

Part b) is more conceptual. Consider the forces acting on the bicycle. The normal force and gravitational acceleration are both directed vertically, so there can be no contribution from them. The only force that can act parallel to the surface is the force of friction!

In fact, static friction is what propels a wheeled vehicle forward regardless of whether it is executing a turn or not. The friction is static since the bottom of the wheel is momentarily at rest with the ground and always tends to accelerate backwards with respect to the ground, so the force of static friction is forward! Friction back at it again, doing unexpected things.

Consider a bicycle going around a circular track of radius $15 ~\textrm{m}$ at $12 ~\textrm{m/s}$. The bicycle and rider have a combined mass of $70 ~\textrm{kg}$.

a) What is the centripetal force that must be acting on the system?

b) What force supplies this centripetal force?

Part a) is a direct calculation and is quite simple to do.

$$F_c= m\frac{v^2}{r}=672 ~\textrm{N}$$

Part b) is more conceptual. Consider the forces acting on the bicycle. The normal force and gravitational acceleration are both directed vertically, so there can be no contribution from them. The only force that can act parallel to the surface is the force of friction!

In fact, static friction is what propels a wheeled vehicle forward regardless of whether it is executing a turn or not. The friction is static since the bottom of the wheel is momentarily at rest with the ground and always tends to accelerate backwards with respect to the ground, so the force of static friction is forward! Friction back at it again, doing unexpected things.

Banked Curves

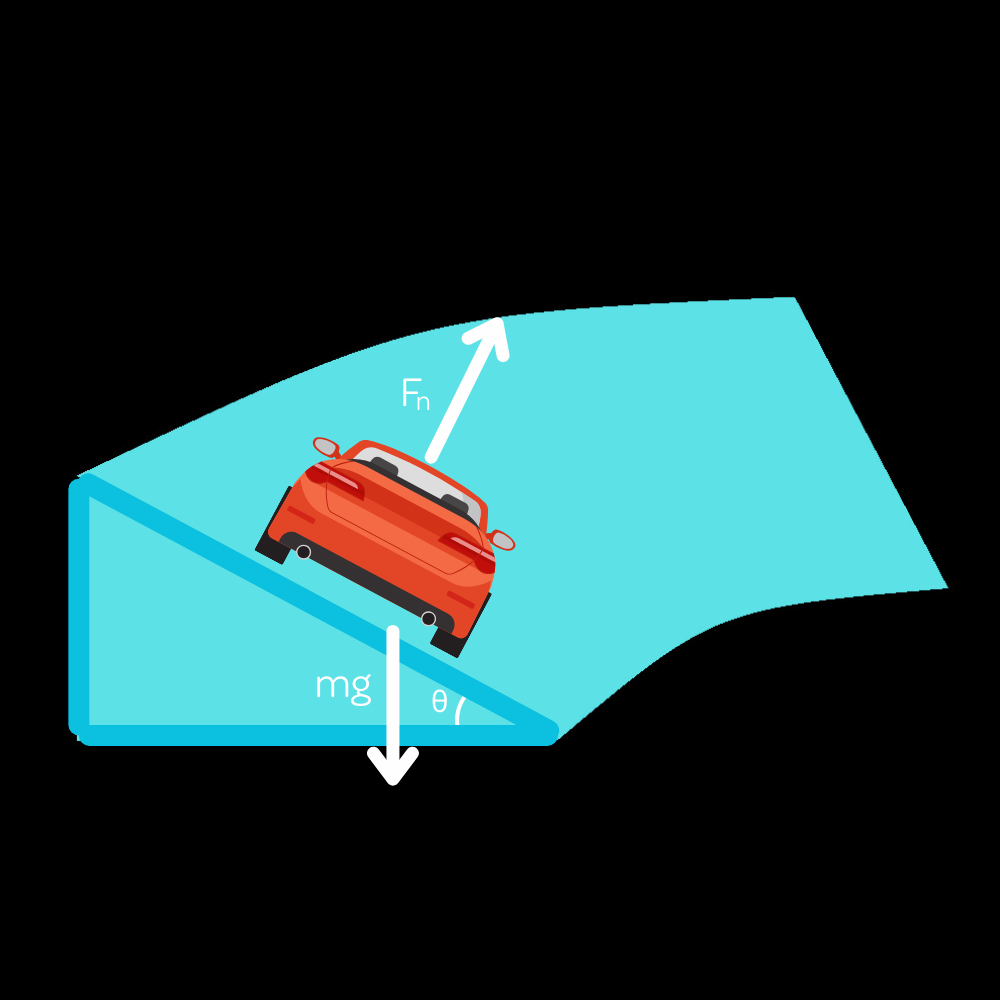

Now, we should consider the special case of a banked curve. This isn't an easy calculation, so instead of making this a problem I'll walk you through it.

This is essentially just a curved inclined plane, so we can really just treat it the same way. Do note, however, that the centripetal force is directed horizontally with respect to the ground and not directed down the incline. In a case like this, it is possible for UCM to occur without any frictional forces, unlike with a flat circle. This is why many road engineers bank their curves to make them safe to drive across at higher speeds. (Or so I've heard, I'm not a road engineer.)

Analysis

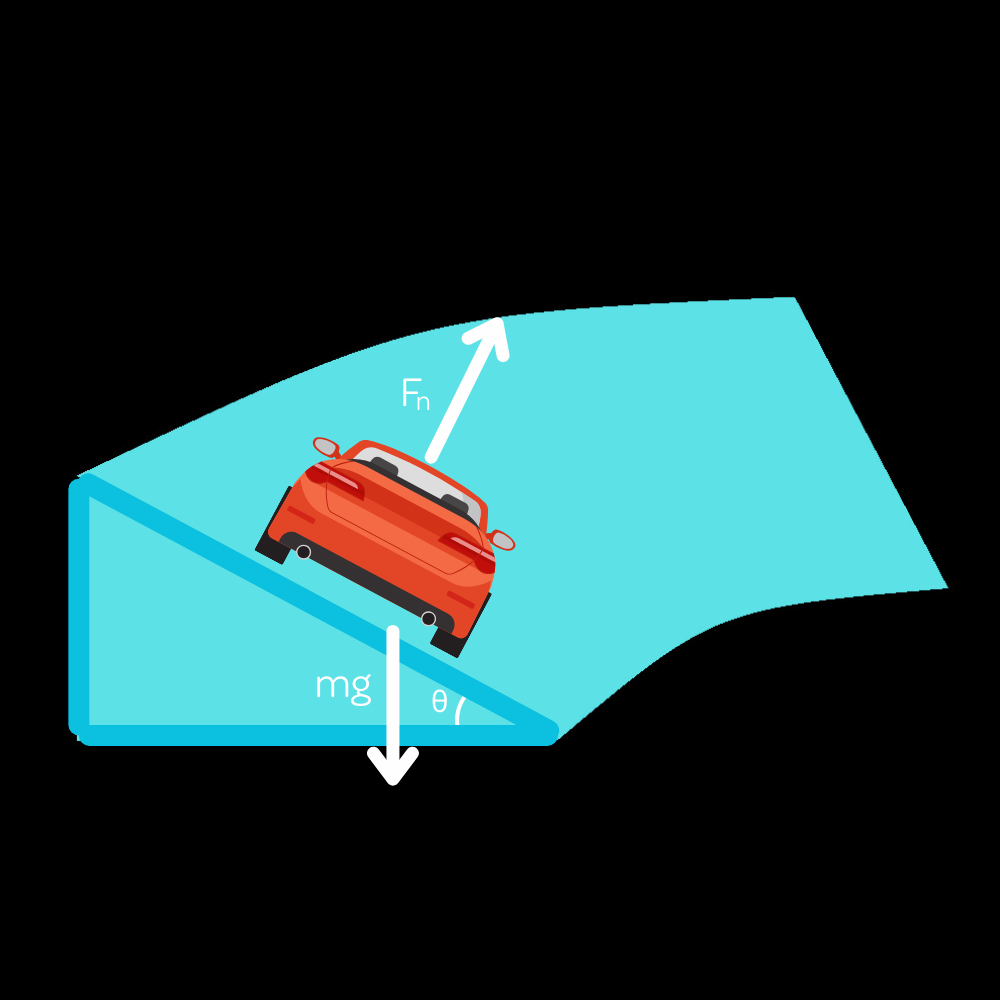

Let’s assume that the curve is banked at an arbitrary angle $\theta$ less than 90 degrees and has a radius $r$, measured from the center of the circle that the object traces out as it moves. What is the range of speeds such that a car can safely execute the turn, assuming no frictional forces up or down the incline?The weight of the object cannot contribute to the centripetal acceleration since it is always perpendicular to the radius of the imaginary horizontal circle the object traces out as it moves along its path. The only other force in this case, then, is $F_n$. In this scenario, it is easier to work with the horizontal and vertical axes rather than the axes along the plane since the only acceleration is in the horizontal direction.

You should recall that the angle between $mg$ and the axis perpendicular to the plane (which $F_n$ lies on) is $\theta$. By the vertical angles theorem, the angle between $F_n$ and the vertical axis is also $\theta$. See, geometry isn’t completely useless.

Since the car does not accelerate in the vertical direction, we can write $F_n \cos\theta = mg$, which is NOT the same as the result $F_n=mg\cos\theta$ for an object sliding down an inclined plane (despite how physically similar the two scenarios look)! Following from this, we have $F_n=mg/\cos\theta$.

The component of $F_n$ that can contribute to the centripetal acceleration is the horizontal component, or $F_nsin\theta$. Using this and the previously derived result, we can write:

$$ma_c=mg\dfrac{\sin\theta}{\cos\theta}=mg \tan\theta$$ $$a_c= g\tan\theta$$

And, since $a_c=v^2/r$,

$$v=\sqrt{gr\tan\theta}$$

This is a very constraining condition, only allowing for a single possible speed for a given curve. It is more realistic to consider friction, which would allow for a range of speeds. The frictional effects are all static if we consider a car (unless the car's tires are slipping, which would not be ideal), but to simplify I will define the coefficient of static and kinetic friction to be $\mu$. Now, find the range of values for $v$ where the car does not move up or down the incline.

Analysis With Friction

The range of values comes from the fact that friction is directed either up or down the incline, depending on $v$. Don't worry too much about this detail for now. We can simply first assume the case of friction up the incline and solve it.The expression: $$F_s=\mu F_n$$ still holds, as always. By doing force analysis, we write down a set of two equations using the horizontal and vertical axes:

$$F_s sin\theta +F_n \cos \theta = mg$$ $$m\dfrac{v^2}{r}=F_n \sin\theta - F_s \cos\theta$$

We can reduce these equations to:

$$F_n(\mu \sin\theta + \cos \theta) = mg$$ $$m\dfrac{v^2}{r}=F_n (\sin\theta - \mu \cos\theta)$$

Eliminating $F_n$ gives:

$$\dfrac {v^2}{gr}= \dfrac {\sin\theta - \mu \cos\theta}{\mu \sin\theta + \cos \theta}$$

Since we assumed the friction is up the incline, this is the lower bound. The way to know this is to realize that friction is attempting to keep the car from slipping down the incline if it's directed upwards, and this only occurs if the car is going slow. This is because less centripetal force is required if the vehicle is moving slower, and thus the friction force must be opposed to the component of the normal force that is providing the centripetal force. Therefore, we can write the first condition:

$$v<\sqrt{gr\dfrac{\tan \theta - \mu}{\mu \tan\theta + 1}}$$

This is the lower bound, and we can find the upper bound by repeating the calculation with friction in the other direction. However, if you’re lazy like me, you can just reverse the signs within the dimensionless term (the term with $\mu$ in it), which works because of how vectors work. (If you don’t understand, I either recommend reviewing vectors or just brute forcing it to prove it to yourself.) What I mean is:

$$\sqrt{gr\dfrac{\tan \theta - \mu}{\mu \tan\theta + 1}}< v < \sqrt{gr\dfrac{\tan \theta + \mu}{1 - \mu \tan\theta}}$$

A quite complex result.

Now there is the case of non-uniform circular motion, most simply in the case of a vertical circle.

Banked Curves

Conceptually, there is one special type of circular motion scenario that is important to consider. If you've ever paid attention while driving or being driven, you'll notice that sometimes, a turn on the freeway will be tilted at an angle. This actually has a physical reason behind it, helping to keep the cars from sliding off the road and allowing them to navigate the turn at a higher speed.See, normally, it is the force of static friction that both propels cars forwards and provides the centripetal force during turns. There is an explanation for why this is. Consider a car driving in a horizontal circle. Neither the gravitational or normal force are in the right direction to provide the centripetal force. The only force that can act parallel to a surface is the force of friction! There is also an explanation for how static friction propels a wheeled vehicle forward regardless of whether it is executing a turn or not. The friction is static since the bottom of the wheel is momentarily at rest with the ground (think about how the wheel doesn't slip!) and that point always tends to accelerate backwards with respect to the ground, so the force of static friction is forward! Think about it more until you understand this.

Now, we're going to show a diagram of the banked turn to drive home what it really is:

Force Analysis

Now, let's look at the forces involved. The weight of the object cannot contribute to the centripetal acceleration since it is always perpendicular to the radius of the imaginary horizontal circle the object traces out as it moves along its path. The only other force in this case, then, is $F_n$. In this scenario, it is easier to work with the horizontal and vertical axes rather than the axes along the plane since the only acceleration is in the horizontal direction.

The range of values comes from the fact that friction is directed either up or down the incline, depending on $v$. The way to solve problems where the direction of friction can be uncertain is to simply assume a direction first and find a result, then go back and assume friction in the other direction. Qualitatively, we know that friction will be directed up the incline if the speed is low, as a smaller centripetal force is needed in that case. The inverse is true as well; if speeds are high friction will be directed down the incline to provide additional centripetal force. If you've been in or driven a car (or just know how a thing with wheels behaves on a slope), you might have some intuition for this.

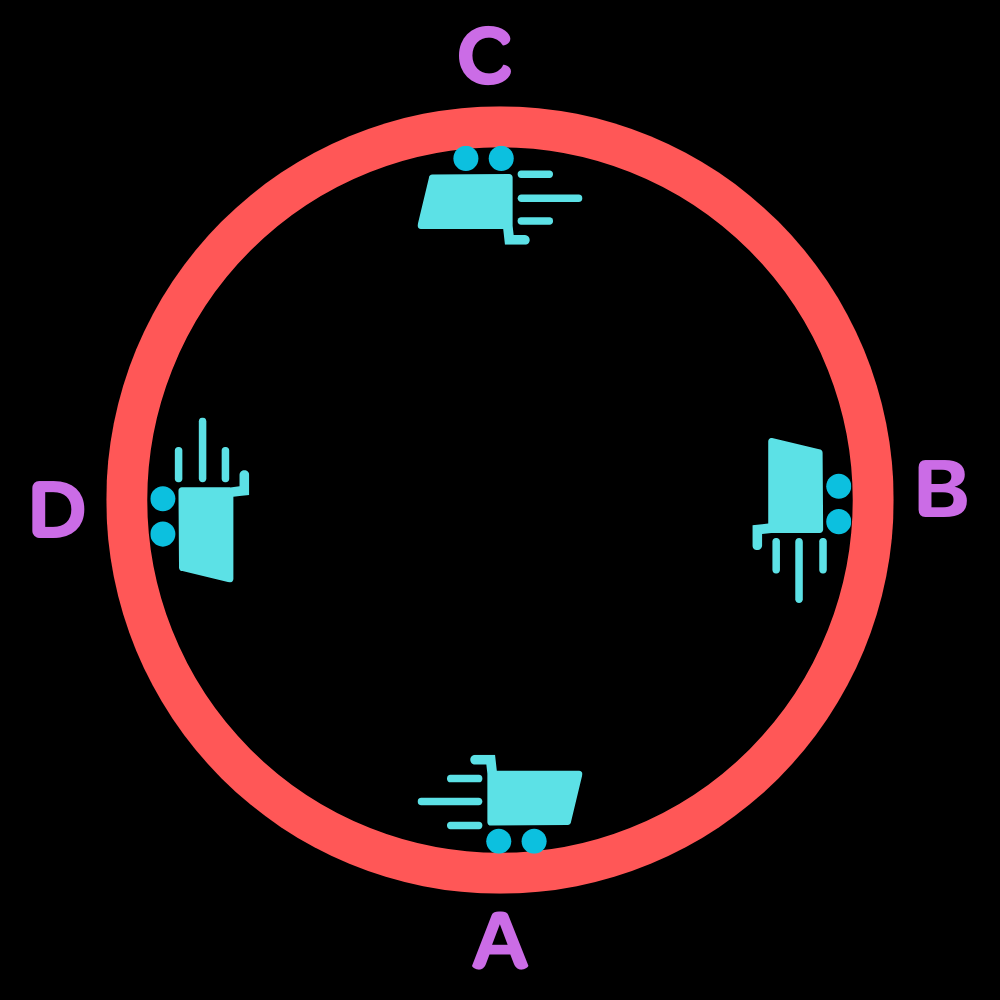

Vertical Circular Motion

We've dealt with horizontal circular motion and even the banked curve, but there is one more case: that of vertical circular motion. A simple example of this is when you swing a ball on a string in a vertical circle, or when a roller coaster goes through a loop-de-loop.This kind of circular motion is not uniform, as the speed of the object changes throughout the motion. The gravitational force is always directed downwards, but the centripetal force must always be towards the center of the circle. This means that while you travel upwards, your speed will decrease due to the gravitational force, and when you travel downwards, your speed will increase due to the gravitational force.

Most of the time, only a select few points in the motion are considered, such as the top and bottom of the circle. The top of the circle is the most interesting point, as it is the point where the ball is moving the slowest and thus the centripetal force required is the least. The ball, however, must still be moving with enough velocity to not fall out of the vertical circle. We are going to analyze this result, but first a diagram:

Analysis

We are going to analyze every point labelled, but the top and bottom points are the most important. We'll first start with the bottom point, labelled A. This is the simplest point to analyze. We'll say the circle has a radius of $R$ and the object a mass $m$.The object must enter the circle with some velocity $v_0$ at the bottom point. At this point, only the gravitational and normal forces are acting on the object. The centripetal force must be upwards, so the normal force must be greater than the gravitational force. Their difference must equal the centripetal force.

$$F_n - mg = m\dfrac{ {v_0}^2}{R}$$

This means that the normal force is:

$$F_n = mg + m\dfrac{ {v_0}^2}{R}$$

This is the only piece of information we can analyze at this point. While it is possible to find the minimum possible velocity to successfully complete the circle, that approach requires the concept of energy.

Now, we will analyze the top point, labelled C. This is the most interesting point since it is the point where the object is moving the slowest and is the critical point for the object to not fall out of the circle. If it doesn't fall out here, it won't fall out anywhere else.

At this point, the gravitational force can contribute to the centripetal force since it's in the correct direction. The normal force may also contribute, but it is not required to! At velocities above the critical velocity, there will be some normal force, but at the critical velocity the object is about to fall out of the circle. Therefore, we can conclude that the normal force will be zero at the critical velocity.

This allows us to solve for the critical velocity $v_c$. When the normal force is zero, the centripetal force is entirely provided by the gravitational force. We can write:

$$mg = m\dfrac{ {v_c}^2}{R}$$ $$ v_c = \sqrt{gR}$$

This is the minimum velocity that the object must have at the top of the circle in order not to fall out.

The points B and D are pretty similar and not worth mathematically analyzing in depth. In these cases, gravity is completely tangential and cannot provide any centripetal force, which means all centripetal force is provided by the normal force. The normal force can vary pretty much infinitely in our theoretical cases (though in real life the material has stress limits), so we can just conclude that the normal force is equal to the required centripetal force at these points.

However, since gravity is directed tangentially to the circle at both points, it produces a tangential acceleration equal to $g$ downwards at both points. This has varying results depending on which stage of the motion the object is in. It acts to slow down the object at point B, while it speeds it up at point D. However, due to a neat quirk that will be explained in the energy unit, the speeds at these two points are equal.

Conclusion

I'll bet all this talk has your head going around in circles (ha ha, get it?). Now, let's slightly pivot our angle on these problems and introduce a new method of analyzing them. You will be reunited with a force that I said wasn't real at the beginning of this unit, and learn about mysterious forces that aren't actually real but somehow still exist (in calculations). If you're ready to dive into the world of fiction, go on to the next lesson! We are only going to analyze the top and bottom points of the circle, as they are the most important. These are marked as A and C on the diagram, respectively. Let's start with the bottom point A since it's the simplest.At this point, the object enters the circle with some velocity $v_0$. Only the gravitational and normal forces are acting on the object. The centripetal force must be upwards, and only the normal force is upwards while the gravitational is downwards. Therefore, the normal force has to be greater than the gravitational force in order for circular motion to occur. Since they are the only two forces, the difference of the two is the required centripetal force.

$$F_n - mg = m\dfrac{ {v_0}^2}{R}$$

This means that the normal force is:

$$F_n = mg + m\dfrac{ {v_0}^2}{R}$$

This is result that's pretty simple to derive, but don't worry if the math intimidates you. Knowing the things I said in the previous paragraph is enough to understand this result and the concepts behind it.

Now, we'll deal with the pesky top point C. This is actually the most interesting point, since it's a critical point for the object to not fall out of the circle. If it doesn't fall out here, it can't fall out anywhere else.

At this point, the gravitational force can contribute to the centripetal force since it's in the correct direction. The normal force may also contribute, but it is not required to! At velocities above the critical velocity, there will be some normal force, but at the critical velocity the object is about to fall out of the circle, meaning it's just barely losing contact with the surface of the loop. Therefore, we can conclude that the normal force will be zero at the critical velocity.

This critical velocity can be derived quite easily by setting the normal force to zero. When the normal force is zero, the centripetal force is entirely provided by the gravitational force. We can write:

$$mg = m\dfrac{ {v_c}^2}{R}$$ $$ v_c = \sqrt{gR}$$

This result is important to know, as it is the minimum velocity that the object must have at the top of the circle in order not to fall out.